The Rational Cloning: Mosaic Musings #2

Disinflation → Inflation Inflection Point? [Inflation Crisis Series]

History has repeatedly shown that people tend to have a strong bias to believe that the future will look like a modestly modified version of the past even when the evidence and common sense point toward big changes.

I believe that’s what’s going on and that we are in the part of the cycle when most people’s psychology and actions are shifting from deeply imbued disinflationary ones to inflationary ones.

-Ray Dalio

Mosaic Musings is a new weekly edition that dives into one topic (probably one I am currently obsessing over). While doing research, I like to gather information from a variety of sources and collect it in one place, so Mosaic Musings will be exactly that: a collection of ideas from various sources about one topic that weave together to form an investment thesis.

Hopefully you can go to bed a little smarter after reading and maybe even make a few bucks.

Definitions

Inflation: decline of purchasing power of a given currency over time

Deflation: increase of purchasing power of a given currency over time

Disinflation: temporary slowing of the pace of price inflation (unlike inflation and deflation, which refer to the direction of prices, disinflation refers to the rate of change in the rate of inflation)

Ray Dalio’s post that came out on February 15, 2022 is the inspiration behind today’s musings. Specifically, it was the phrase “people’s psychology and actions are shifting from deeply imbued disinflationary ones to inflationary ones” that caught my attention.

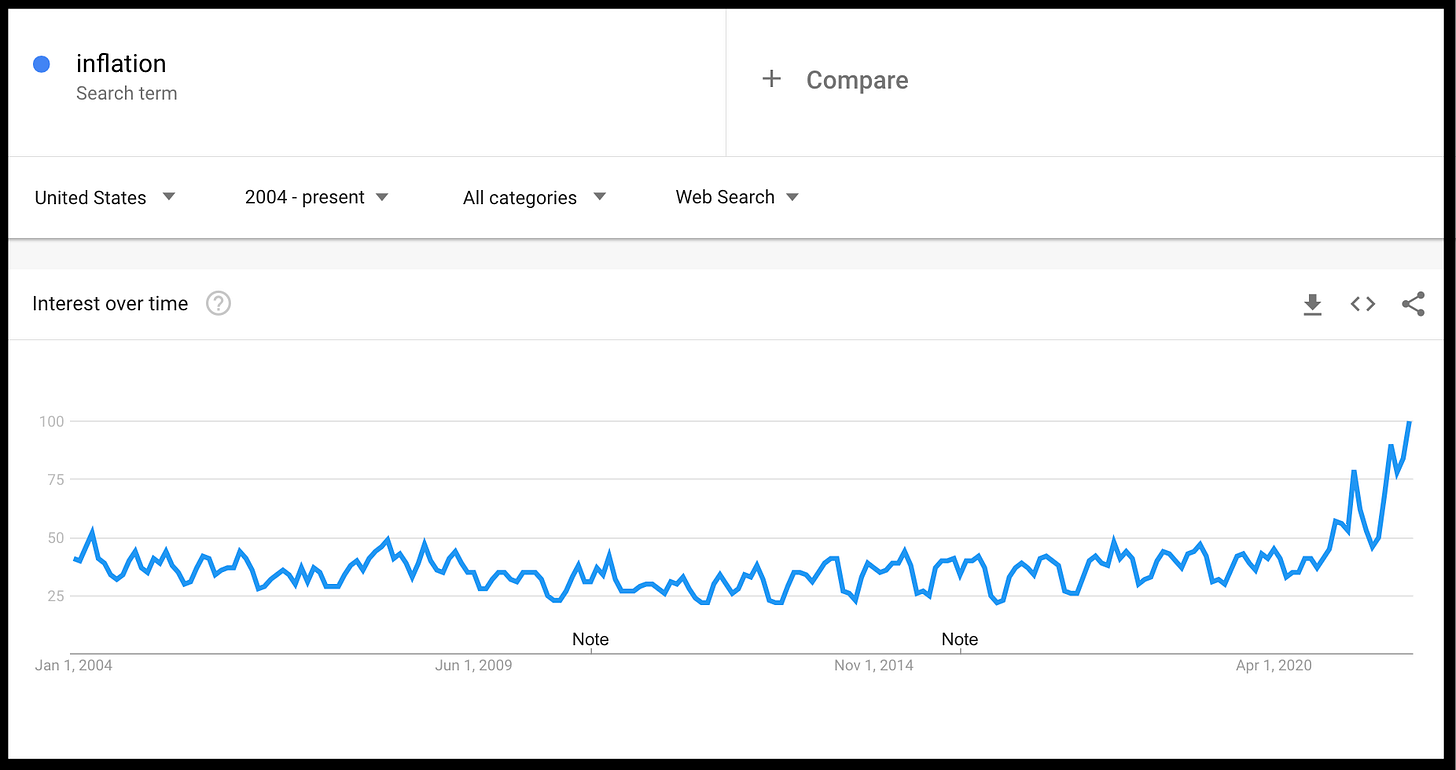

Are we really at the inflection point between disinflation and inflation?

CPI numbers in the United States are at a 40 year high of 7.5%. If you assume the CPI numbers are a little unrealistic (e.g. CPI assumes substitution and hedonic adjustments), we can safely assume that the real inflation numbers are higher. I think people are realizing to realize that maybe inflation (like wages) is sticky and here to stay.

The inflationary dragon might finally be waking up.

If that happens, a 40 year period of disinflation has left indices (and most people’s portfolio) frighteningly fragile to an inflationary environment.

Before we dive in, what percentage of the S&P 500 do you think consists of inflation hedges/beneficiaries (e,g, hard assets, energy, land, precious metals, etc.)?

This musing will be split into two sections:

Arguments for both transitory and persistent inflation

How to prepare for inflation

Transitory or Persistent Inflation?

Transitory Inflation Arguments

From this FT article:

The Fed may move faster and farther than anticipated early in 2022 to retain credibility as an inflation fighter. But fiscal drag, shrinking savings and weak foreign demand are likely to ease an overheated economy. This, and improving supply chains, will reduce inflation pressures. Summers and others were right in 2021, but I see the balance tipping within six months.

I’m signing up for another year as a member of Team Transitory.

Unemployed respondents to a survey by Indeed.com said their financial cushion was one of the top three reasons for not urgently seeking a job. As those savings run down, many who dropped out of the labour force will try to return, boosting labour supply and easing upward pressure on wages, and therefore prices.

Even limited Fed rate hikes will increase borrowing costs in 2022. Ten-year US Treasury yields are rising, and it’s hard to argue the investment environment will improve in 2022. The dollar will strengthen, pushing down inflation and exports.

Order backlogs and supply delivery times have improved in recent months. According to the New York Fed’s new Global Supply Chains Pressure Index, supply-chain issues “have peaked and might start to moderate somewhat going forward”. That, too, will lead to US inflation abating later this year.

Persistent Inflation Arguments

In their Q4 2021 Letter, Horizon Kinetics offers a logical line of reasoning for persistent, systemic inflation:

So, the inflation we see today is only the very beginning of the process. Inflationary events will continue to develop, and the news and the public discussion will continue to lag behind.

Know a Change of Era When You See One

Here is a list of some systemic conditions that have occurred in the past 40 years. Consider, for any individual factor – or for all of them in concert – the massive benefit they’ve been for financial assets, especially stocks and bonds.

A 40-year, 90% decline in interest rates. They can only go from 14% to 1%, once.

40 years of exporting of inflation – labor and manufacturing costs – through the opening of previously closed developing-nation markets. Not only can’t that be repeated, many of those nations have evolved technologically and are now competitors.

A 40-year, 25%-point decline in the corporate tax rate. With today’s 21%, that certainly can’t be repeated, unless the tax rate becomes a negative figure.

A 40-year trend of declining commodity costs, including:

A45% decline in the price of oil

The opening of the Russian/formerly Soviet hard commodity supply market

A decade-long decline in a broad swath of essential other commodities

The 40-year incalculable corporate cost/benefit impact of the appearance and ascendance of both the personal computer operating system and the internet.

A 30-year trend of rising corporate margins, to levels never before seen.

An all-time historic high stock market valuation, via the simplest, most direct calculation: the total value of the stock market as a % of GDP.

If all those factors simply stop becoming more extreme – no negative interest rates or negative tax rates, etc. – if they were just to stay where they are, then their beneficent disinflationary and profit and valuation influences would cease. The future would be a lot less wonderful than the past. That’s all that’s necessary.

But they’re not staying still. The two most important inflation variables, monetary policy and commodities prices, are heading in the wrong direction. They are already beyond certain limits and are becoming actively inflationary.

Monetary Policy: There’s now so much debt, that we’re probably past the tipping point for the Federal Reserve to permit interest rate to rise. Why can’t they? Because they would unleash a financial crisis. How?

Total debt in the U.S. is now $85 trillion. That’s everything from Federal and local debt to auto loans, credit cards and mortgages. The average interest cost is 4.1%. What if the Fed were to let rates rise by 2% points. Doesn’t seem like a lot. It would just bring the 10-year yield to 3.7%.

Just for simplifying purposes, though, let’s say that the 2% immediately filtered through all the different types and maturities of debt. That means that the entire country experiences an increased interest expense burden of 2% x $85 trillion of debt, which equals $1.70 trillion.

$1.7 trillion of additional interest expense would reduce our $23 trillion of GDP by 7.4%. A significant recession is a -3% GDP contraction. The Great Recession of 2008/2009, following the subprime mortgage crisis, which was a true financial crisis, was a -5.1% contraction.

To make it even more relatable, let’s say the additional $1.7 trillion of interest expense were somehow all allocated only to oil. The U.S. consumes roughly 20 million barrels of oil per day. That’s 7.3 billion barrels a year. If we pay an additional $1.7 trillion per year for that oil, that would be an additional $232 per barrel. Since oil is about $85 now, that would be $317/barrel oil.

Which is why the central bank’s (any central bank’s) standard recourse is to play out this self-reinforcing monetary debasement game for as long as it takes to ‘grow’ out of the problem. And it can grow out of the problem. It’s just that it comes at a cost… that cost is monetary-based inflation, or currency debasement.

Commodities Price: Unfortunately, we’ve also begun to experience commodity-shortage based inflation. And that is just as serious and just as intractable. We’ve had this discussion so repeatedly, that I’m wary of overdoing it. So perhaps just one fresh example, different than previous ones, will serve as a proxy for the challenge of rising global resource scarcity.

Back to the topic of monetary-based inflation and currency debasement. In the same Ray Dalio piece, he seems to agree:

In virtually every case, the government contributes to the accumulation of debt with its actions and by becoming a large debtor itself. When the debt bubble bursts, the government bails itself and others out by buying assets and/or printing money and devaluing it. The larger the debt crisis, the more that is true.

When one can manufacture money and credit and pass them out to everyone to make them happy, it is very hard to resist the temptation to do so. It is a classic financial move. Throughout history, rulers have run up debts that won’t come due until long after their own reigns are over, leaving it to their successors to pay the bill.

That is why central banks always end up printing money and devaluing.

When governments print a lot of money and buy a lot of debt, they cheapen both, which essentially taxes those who own it, making it easier for debtors and borrowers. When this happens to the point that the holders of money and debt assets realize what is going on, they seek to sell their debt assets and/or borrow money to get into debt they can pay back with cheap money.

They also often move their wealth into better storeholds, such as gold and certain types of stocks, or to another country not having these problems. At such times central banks have typically continued to print money and buy debt directly or indirectly while outlawing the flow of money into inflation-hedge assets, alternative currencies, and alternative places.

While people tend to believe that a currency is pretty much a permanent thing and that “cash” is the safest asset to hold, that’s not true. All currencies devalue or die, and when they do, cash and bonds (which are promises to receive currency) are devalued or wiped out. That is because printing a lot of currency and devaluing debt is the most expedient way of reducing or wiping out debt burdens.

In the recent Daily Journal annual meeting, Charlie Munger also seems to agree that fiat is going to die (which made a lot of noise in the crypto community):

How to prepare for inflation?

You can’t predict. You can prepare. -Howard Marks

Let’s start with S&P 500. Again, from Horizon Kinetics:

At year-end, the totality of traditional inflation hedges in the S&P 500, at about 3%, isn’t hedging anything.

Energy was a 2.7% weight in the S&P 500.

The only metals exposure is 0.16% (Freeport-McMoRan, the copper miner).

The only precious metals exposure is 0.12% (Newmont Mining). Even though those two companies are economically important and quite large, with market caps in the $50 to $60 billion range.

Even the largest four securities exchanges are only 0.46%. These are companies with market caps up to $70 billion. These are important diversifiers in that they have positive revenue and earnings exposure to every sort of economic upset vector: the full range of hard and soft commodities, interest rates, currencies, and volatility.

Not sure if the S&P 500 is the best option for preparing for inflation.

After some digging around, below is a cobbled list of some ideas I’ve found that could function as inflation hedges/beneficiaries:

Asset-Light Companies

Royalty Companies: TPL, BSM, FNV, WPM

Croupiers

Securities Exchanges: CME, CBOE, ICE

Payment Networks: V, MA

Casinos

Energy

Gold/Precious Metals

Commodities

Companies With Pricing Power: tobacco, consumer staples, memberships (Prime, Netflix), certain restaurants (CMG)

Taking on Debt

This post seems to be getting a bit long, so we’ll stop it here.

Mosaic Musings #3 will be dedicated to a deeper dive into specific names/ideas that should hedge/benefit from inflation.

Until next time,

The Rational Cloner